What Was Sinclair's Purpose In Writing The Jungle

CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS FOUNDATION

Bill of Rights in Action

FALL 2008 (Volume 24, No. 1)

Reform

Communism, Capitalism, and Democracy in China | Upton Sinclair's The Jungle | John Dewey and the Reconstruction of American Democracy

Upton Sinclair's The Jungle:

Muckraking the Meat-Packing Industry

Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle to expose the appalling working conditions in the meat-packing industry. His description of diseased, rotten, and contaminated meat shocked the public and led to new federal food safety laws.

Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle to expose the appalling working conditions in the meat-packing industry. His description of diseased, rotten, and contaminated meat shocked the public and led to new federal food safety laws.

Before the turn of the 20th century, a major reform movement had emerged in the United States. Known as progressives, the reformers were reacting to problems caused by the rapid growth of factories and cities. Progressives at first concentrated on improving the lives of those living in slums and in getting rid of corruption in government.

By the beginning of the new century, progressives had started to attack huge corporations like Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, and the Armour meat-packing company for their unjust practices. The progressives revealed how these companies eliminated competition, set high prices, and treated workers as "wage slaves."

The progressives differed, however, on how best to control these big businesses. Some progressives wanted to break up the large corporations with anti-monopoly laws. Others thought state or federal government regulation would be more effective. A growing minority argued in favor of socialism, the public ownership of industries. The owners of the large industries dismissed all these proposals: They demanded that they be left alone to run their businesses as they saw fit.

Theodore Roosevelt was the president when the progressive reformers were gathering strength. Assuming the presidency in 1901 after the assassination of William McKinley, he remained in the White House until 1909. Roosevelt favored large-scale enterprises. "The corporation is here to stay," he declared. But he favored government regulation of them "with due regard of the public as a whole."

Roosevelt did not always approve of the progressive-minded journalists and other writers who exposed what they saw as corporate injustices. When David Phillips, a progressive journalist, wrote a series of articles that attacked U.S. senators of both political parties for serving the interests of big business rather than the people, President Roosevelt thought Phillips had gone too far. He referred to him as a man with a "muck-rake."

Even so, Roosevelt had to admit, "There is filth on the floor, and it must be scraped up with the muck-rake." The term "muckraker" caught on. It referred to investigative writers who uncovered the dark side of society.

Few places had more "filth on the floor" than the meat- packing houses of Chicago. Upton Sinclair, a largely unknown fiction writer, became an "accidental muckraker" when he wrote a novel about the meat-packing industry.

Packingtown

By the early 1900s, four major meat-packing corporations had bought out the many small slaughterhouse companies throughout the United States. Because they were so large, the Armour, Swift, Morris, and National Packing companies could dictate prices to cattle ranchers, feed growers, and consumers.

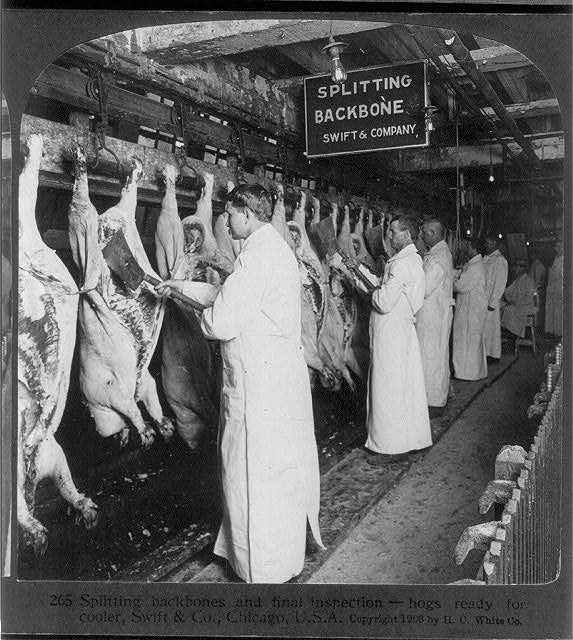

The Big Four meat-packing companies centralized their operations in a few cities. Largest of all was the meat-packing industry in Chicago. It spread through acres of stockyards, feed lots, slaughterhouses, and meat-processing plants. Together with the nearby housing area where the workers lived, this part of Chicago was known as Packingtown.

Long before Henry Ford adapted it to automobile production, meat packers had developed the first industrial assembly line. It was more accurately a "disassembly line," requiring nearly 80 separate jobs from the killing of an animal to processing its meat for sale. "Killing gangs" held jobs like "knockers," "rippers," "leg breakers," and "gutters." The animal carcasses moved continuously on hooks until processed into fresh, smoked, salted, pickled, and canned meats. The organs, bones, fat, and other scraps ended up as lard, soap, and fertilizer. The workers said that the meat-packing companies "used everything but the squeal."

Unskilled immigrant men did the backbreaking and often dangerous work, laboring in dark and unventilated rooms, hot in summer and unheated in winter. Many stood all day on floors covered with blood, meat scraps, and foul water, wielding sledgehammers and knives. Women and children over 14 worked at meat trimming, sausage making, and canning.

Most workers earned just pennies per hour and worked 10 hours per day, six days a week. A few skilled workers, however, made as much as 50 cents an hour as "pacesetters," who sped up the assembly line to maximize production. The use of pacesetters caused great discontent among the workers.

By 1904, most of Chicago's packing-house workers were recent immigrants from Poland, Slovakia, and Lithuania. They crowded into tenement apartments and rented rooms in Packingtown, next to the stinking stockyards and four city dumps.

Real estate agents sold some immigrants small houses on credit, knowing that few would be able to keep up with the payments due to job layoffs, pay cuts, or disabling injuries. When an immigrant fell behind in payments, the mortgage holder would foreclose, repaint, and sell the house to another immigrant family.

Upton Sinclair

Born in Baltimore in 1878, Upton Sinclair came from an old Virginia family. The Civil War had wiped out the family's wealth and land holdings. Sinclair's father became a traveling liquor salesman and alcoholic. The future author's mother wanted him to become a minister. At age 5, he wrote his first story. It told about a pig that ate a pin, which ended up in a family's sausage.

When he was 10, Sinclair's family moved to New York City where he went to school and college. While attending Columbia University, he began to sell stories to magazines. He specialized in western, adventure, sports, and war-hero fiction for working-class readers.

Sinclair graduated from Columbia in 1897, and three years later he married Meta Fuller. They had one child. Sinclair began to write novels but had difficulty getting them published.

As he was struggling to make a living as a writer, he began reading about socialism. He came to believe in the idea of a peaceful revolution in which Americans would vote for the government to take over the ownership of big businesses. He joined the Socialist Party in 1903, and a year later he began to write for Appeal to Reason, a socialist magazine.

In 1904, the meat-packer's union in Chicago went on strike, demanding better wages and working conditions. The Big Four companies broke the strike and the union by bringing in strikebreakers, replacements for those on strike. The new workers kept the assembly lines running while the strikers and their families fell into poverty.

The editor of Appeal to Reason suggested that Sinclair write a novel about the strike. Sinclair, at age 26, went to Chicago at the end of 1904 to research the strike and the conditions suffered by the meat-packing workers. He interviewed them, their families, lawyers, doctors, and social workers. He personally observed the appalling conditions inside the meat-packing plants.

The Jungle

The Jungle

The Jungle is Sinclair's fictionalized account of Chicago's Packingtown. The title reflects his view of the brutality he saw in the meat-packing business. The story centered on a young man, Jurgis Rudkis, who had recently immigrated to Chicago with a group of relatives and friends from Lithuania.

Full of hope for a better life, Jurgis married and bought a house on credit. He was elated when he got a job as a "shoveler of guts" at "Durham," a fictional firm based on Armour & Co., the leading Chicago meat packer.

Jurgis soon learned how the company sped up the assembly line to squeeze more work out of the men for the same pay. He discovered the company cheated workers by not paying them anything for working part of an hour.

Jurgis saw men in the pickling room with skin diseases. Men who used knives on the sped-up assembly lines frequently lost fingers. Men who hauled 100-pound hunks of meat crippled their backs. Workers with tuberculosis coughed constantly and spit blood on the floor. Right next to where the meat was processed, workers used primitive toilets with no soap and water to clean their hands. In some areas, no toilets existed, and workers had to urinate in a corner. Lunchrooms were rare, and workers ate where they worked.

Almost as an afterthought, Sinclair included a chapter on how diseased, rotten, and contaminated meat products were processed, doctored by chemicals, and mislabeled for sale to the public. He wrote that workers would process dead, injured, and diseased animals after regular hours when no meat inspectors were around. He explained how pork fat and beef scraps were canned and labeled as "potted chicken."

Sinclair wrote that meat for canning and sausage was piled on the floor before workers carried it off in carts holding sawdust, human spit and urine, rat dung, rat poison, and even dead rats. His most famous description of a meat-packing horror concerned men who fell into steaming lard vats:

. . . and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting,--sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham's Pure Leaf Lard!

Jurgis suffered a series of heart-wrenching misfortunes that began when he was injured on the assembly line. No workers' compensation existed, and the employer was not responsible for people injured on the job. Jurgis' life fell apart, and he lost his wife, son, house, and job.

Then Jurgis met a socialist hotel owner, who hired him as a porter. Jurgis listened to socialist speakers who appeared at the hotel, attended political rallies, and drew inspiration from socialism. Sinclair used the speeches to express his own views about workers voting for socialist candidates to take over the government and end the evils of capitalist greed and "wage slavery."

In the last scene of the novel, Jurgis attended a celebration of socialist election victories in Packingtown. Jurgis was excited and once again hopeful. A speaker, probably modeled after Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, begged the crowd to "Organize! Organize! Organize!" Do this, the speaker shouted, and "Chicago will be ours! Chicago will be ours! CHICAGO WILL BE OURS!"

The Public Reaction

The Jungle was first published in 1905 as a serial in The Appeal to Reason and then as a book in 1906. Sales rocketed. It was an international best-seller, published in 17 languages.

Sinclair was dismayed, however, when the public reacted with outrage about the filthy and falsely labeled meat but ignored the plight of the workers. Meat sales dropped sharply. "I aimed at the public's heart," he said, "and by accident I hit it in the stomach."

Sinclair thought of himself as a novelist, not as a muckraker who investigated and wrote about economic and social injustices. But The Jungle took on a life of its own as one of the great muckraking works of the Progressive Era. Sinclair became an "accidental muckraker."

The White House was bombarded with mail, calling for reform of the meat-packing industry. After reading The Jungle, President Roosevelt invited Sinclair to the White House to discuss it. The president then appointed a special commission to investigate Chicago's slaughterhouses.

The special commission issued its report in May 1906. The report confirmed almost all the horrors that Sinclair had written about. One day, the commissioners witnessed a slaughtered hog that fell part way into a worker toilet. Workers took the carcass out without cleaning it and put it on a hook with the others on the assembly line.

The commissioners criticized existing meat-inspection laws that required only confirming the healthfulness of animals at the time of slaughter. The commissioners recommended that inspections take place at every stage of the processing of meat. They also called for the secretary of agriculture to make rules requiring the "cleanliness and wholesomeness of animal products."

New Federal Food Laws

President Roosevelt called the conditions revealed in the special commission's report "revolting." In a letter to Congress, he declared, "A law is needed which will enable the inspectors of the [Federal] Government to inspect and supervise from the hoof to the can the preparation of the meat food product."

Roosevelt overcame meat-packer opposition and pushed through the Meat Inspection Act of 1906. The law authorized inspectors from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to stop any bad or mislabeled meat from entering interstate and foreign commerce. This law greatly expanded federal government regulation of private enterprise. The meat packers, however, won a provision in the law requiring federal government rather than the companies to pay for the inspection.

Sinclair did not like the law's regulation approach. True to his socialist convictions, he preferred meat-packing plants to be publicly owned and operated by cities, as was commonly the case in Europe.

Passage of the Meat Inspection Act opened the way for Congress to approve a long-blocked law to regulate the sale of most other foods and drugs. For over 20 years, Harvey W. Wiley, chief chemist at the Department of Agriculture, had led a "pure food crusade." He and his "Poison Squad" had tested chemicals added to preserve foods and found many were dangerous to human health. The uproar over The Jungle revived Wiley's lobbying efforts in Congress for federal food and drug regulation.

Roosevelt signed a law regulating foods and drugs on June 30, 1906, the same day he signed the Meat Inspection Act. The Pure Food and Drug Act regulated food additives and prohibited misleading labeling of food and drugs. This law led to the formation of the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The two 1906 laws ended up increasing consumer confidence in the food and drugs they purchased, which benefitted these businesses. The laws also acted as a wedge to expand federal regulation of other industries, one of the strategies to control big business pursued by the progressives.

After The Jungle

The Jungle made Upton Sinclair rich and famous. He started a socialist colony in a 50-room mansion in New Jersey, but the building burned down after a year. In 1911, his wife ran off with a poet. He divorced her, but soon he remarried and moved to California.

During his long life, he wrote more than 90 novels. King Coal was based on the 1914 massacre of striking miners and their families in Colorado. Boston was about the highly publicized case of Sacco and Vancetti, two anarchists tried and executed for bank robbery and murder in the 1920s. His novel Dragon's Teeth, about Nazi Germany, won the 1943 Pulitzer Prize. None of these novels, however, achieved the success of The Jungle.

Several of Sinclair's books were made into movies. In 1914, Hollywood released a movie version of The Jungle. Recently, his work Oil!, which dealt with California's oil industry in the 1920s, was made into the film There Will Be Blood.

During the Great Depression, Sinclair entered electoral politics. He ran for governor of California as a socialist in 1930 and as a Democrat in 1934. In the 1934 election, he promoted a program he called "End Poverty in California." He wanted the state to buy idle factories and abandoned farms and lease them to the unemployed. The Republican incumbent governor, Frank Merriam, defeated him, but Sinclair still won over 800,000 votes (44 percent).

After the death of his second wife in 1961, Sinclair moved to New Jersey to be with his son. He died there in 1968 at age 90.

People still read The Jungle for its realistic picture of conditions in the meat-packing industry at the turn of the 20th century. Like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, The Jungle proved the power of fiction to move a nation.

For Discussion and Writing

1. Why did the existing inspection system fail to guard the safety of meat for human consumption?

2. Why was Upton Sinclair dismayed about the public reaction and legislation that followed publication of The Jungle?

3. How did The Jungle help the progressives achieve their goals?

For Further Reading

Mattson, Kevin. Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century. Hoboken, N. J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

Phelps, Christopher, ed. The Jungle by Upton Sinclair. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.

A C T I V T Y

Working in Packingtown

Upton Sinclair was disappointed that Congress did not address the injustices suffered by workers in Packingtown's meat-packing industry. Take on the role of a muckraker and write an editorial that details the injustices to workers and what Congress should do about them.

A L T E R N A T I V E A C T I V I T Y

A Modern Muckraker

Look at a contemporary problem in the community, state, or nation. Investigate it. Write an editorial on what should be done about it.

What Was Sinclair's Purpose In Writing The Jungle

Source: https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-24-1-b-upton-sinclairs-the-jungle-muckraking-the-meat-packing-industry.html#:~:text=Upton%20Sinclair%20wrote%20The%20Jungle,new%20federal%20food%20safety%20laws.

Posted by: johnstontiledgets.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was Sinclair's Purpose In Writing The Jungle"

Post a Comment